Alex French von der LA Times hat am 7.Mai einen Artikel über Paintball für den Sportteil seiner Zeitung veröffentlicht. Darin wird in der Hauptsache auf der falsche "Kriegsspiel-Image" des Paintballsports eingegangen. Aber auch das Team Dynasty ist ein Thema und wird mit einigen Bildern sowie einignen Absätzen über die Erfolge und den Lebensstil der Jungs porträtiert:

War Games

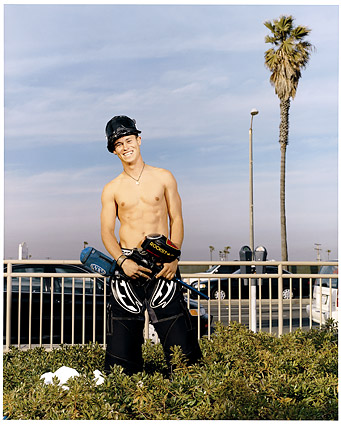

If you were lucky enough to be a member of the San Diego Dynasty, the most dominant team in the 25-year history of competitive paintball, you would almost never wear a shirt. Your torso would be chiseled, as bronze and dark as an old penny, and dappled with round welt scars like cheetah spots. You would wear Dolce & Gabbana sunglasses, nylon board shorts and shiny sterling rings on your fingers and thumbs. You probably wouldn't have to work a day job, but you might anyway, perhaps building custom cars or smashing stuff at construction sites. You would live in the Pacific Beach section of San Diego, where the party meets the ocean.

Cruising the main thoroughfares—Grand and Garnet—from east to west, you'd pass long stretches of sky-high palms, beach sundry stores, upscale Cali-Mex cantinas, wood patio bars and 24-hour taco shops, all the way west to Mission Boulevard and the boardwalk, where vagrants with dreadlocked beards and beet-red skin camp, and thready-veined boys on long boards hiss past bikini-clad girls on beach cruisers with 12-packs of Pacifico cradled in handlebar baskets. You would be one of the best paintballers on earth, a supernova in a sport most people have no idea exists. Seeing your picture in paintball magazines would be old news, though you would never grow tired of it. Nor would you grow tired of seeing yourself in paintball videos or signing autographs for kids who idolize you with the same intensity that I idolized Roger Clemens when I was about the age of most Dynasty fans—between 9 and 16. You would have groupies. The pages of your passport would be covered with stamps from exotic locations, places such as Buenos Aires and Malaysia and Majorca. You would think of the other members of Dynasty less as teammates and more as brothers, and you would inform people of that fact often—that you love each other very, very much. If you were lucky enough to be one of the members of Team Dynasty, you would have a certain awareness that you have been blessed by the gods.

Chances are, when most people think about paintball, they think: war games. They think about rednecks hiding in the forest disguised as bushes and wielding markers (paintball-speak for guns) that look like real assault weapons. If that is indeed the case, then they don't know that paintball is the third most popular action sport in the world (behind skateboarding and in-line skating, but ahead of snowboarding, BMX biking and surfing). Nearly 10 million Americans (predominately male) participate in the sport, though only 6% of them play competitively.

The game is, essentially, capture-the-flag, but with more strategy. Competitive paintball is played in a number of formats; depending on the tournament, teams may play with three, five, seven or even 10 members per team. Instead of rocks and trees, the pros seek cover behind brightly colored inflatable bunkers that sound a hollow ping when hit by a high-velocity projectile. When a player is struck by a paintball, whether it's on the head, chest, foot or on part of his or her equipment, that player is eliminated. In seven-man paintball, the most popular format, the field is always 180 feet long and 100 feet wide, but the number of bunkers—35 to 40 are routinely used—and their arrangement on the field vary from one tournament to the next.

Paintball's massive audience moved ESPN to produce an eight-episode series of the U.S. Paintball Championships from Miami, which currently is airing. The sport is a billion-dollar-a-year retail industry, and the pages of a handful of magazines devoted to pro paintball often feature Dynasty's Alex Fraige, Ryan Greenspan, Angel Fragoza, Yosh Rau, Quincy Boayes, Johnny Perchak and Brian "B.C." Cole hawking apparel and high-tech markers that look more like gas pump handles than machine guns. These advertisements lay bare Dynasty's accomplishments: four World Championships and three Triple Crowns, a title that requires winning the professional division of the American Series, the European Series and the World Series. No team had ever won the Triple Crown before Dynasty.

To those outside the paintball community, the irony accompanying the public adulation surrounding Team Dynasty is that this group of young men, who are renowned for winning pantomime battles, is flourishing in the heart of San Diego, a community that is responsible for training real soldiers and that knows, perhaps better than most, that war is not a game.

Friends asked me several times while I was researching this article: "Do you think those paintball dudes would totally kick ass in Iraq?"

It's the type of question that infuriates Team Dynasty members and paintball advocates who spend a lot of time fighting the idea that paintball is a dangerous war game, part of our culture of violence. Such perceptions prevent the sport from being embraced by the mainstream, they say.

But paintball wasn't intended to be a mainstream pastime. It was a survival game conceived to settle a dispute between two friends, a New York stock trader named Hayes Noel and a writer from New Hampshire named Charles Gaines. According to a 2004 Sports Illustrated article by Gaines, Noel believed that the survival instincts he'd learned living on Manhattan's Upper East Side and working on the trading floor would outperform those of Gaines, not just in an urban environment but also in the woods, an environment in which Gaines had been raised, and with which Noel was almost wholly unfamiliar.

To settle the bet, Gaines, Noel and 10 others—including a ski shop owner, a forester and three writers—took to the woods of New Hampshire in June 1981. Each man was dressed in camouflage and shop goggles and was equipped with a Nel-Spot 007 bolt-action pistol (the kind used by ranchers to mark cattle), a supply of paintballs, extra CO2 cartridges, a compass and a map of the 100-acre game site indicating the whereabouts of four flag stations and home base. Twelve flags hung at each station. The objective was to be the first man to arrive at home base with four different colored flags and without having been shot by another player. According to Gaines, stockbroker Noel spent most of the afternoon cowering in a bush. And the forester, who never fired a single shot and was never seen by another player, won the game.

Following the competition, one of the writer-participants, Bob Jones, wrote the first Sports Illustrated piece about the game; later the other two scribes had articles published in Time and Sports Afield. All three reflected on the unbelievable adrenaline rush that accompanied the hunt. Each article was met by an overwhelming number of letters from readers requesting instructions on how they, too, could play. Gaines, Hayes and ski shop owner Bob Gurnsey responded by selling a starter kit that included a Nel-Spot pistol, paintballs, a compass, goggles and a rule book. They called their creation the National Survival Game. Before long, it would be called paintball. It took practically no time for the game to find its way to Canada, Australia, France and Denmark. These days paintball is played in more than 50 countries.

There are a number of compelling anthropological theories about why it became so popular in the U.S. One is that paintball caters to the American infatuation with guns. Social scientists such as MIT's Hugh Gusterson say this fascination has been hard-wired into our collective psyche. "America's obsession with guns and gunplay has its origins on the Wild West frontier. All real men needed to know how to use a gun—it was necessary to their survival," he says. "Now, it's more necessary for men to have mathematical and linguistic skills, but the fascination with guns has endured."

In 1994, James William Gibson, a sociologist at Cal State Long Beach, published a book called "Warrior Dreams." Gibson argued that in the post-Vietnam years of the late 1970s and early 1980s, a new paramilitary culture took hold of America. It was a time of "Rambo," pulp action novels, military thrillers and magazines such as Solider of Fortune, and those generally depicted good men acting alone or in small groups—and beyond the aegis of a corrupt command authority—to defeat evil men in armed combat. It offered men a fantasy identity as powerful warriors capable of healing the wounds of defeat in Vietnam and battling other perceived foes, such as liberals, feminists and illegal immigrants.

As part of his research, Gibson played paintball at a complex where one course had been designed to resemble a Vietnam village and another to look like the crash site of a Nicaraguan supply plane. "This was definitely a war game," he recalls, and he didn't find that surprising. "From the time of the Greeks up until firearms became fairly reliable in the 18th century, sports like wrestling, fencing and archery were also a form of combat training." As early as the late 1980s, paintball players were abandoning fatigues in favor of motocross clothing resembling the uniforms worn today by Dynasty and other professional teams. Governing bodies such as the National Professional Paintball League were formed to regulate play. To rid the sport of the stigma of violence, insiders began referring to paintball guns as markers. And bunkers were redesigned to look less like military installations and more like playground toys.

For all that, Gibson has reservations about paintball as a sport. "The problem," he says, "is that you're still drawing on somebody."

Proponents of the modern game wave off such criticism. "Paintball isn't a war game," says Eric Crandall, a former paintball player and Team Dynasty's longtime manager. Players consider themselves to be athletes. If they wanted to go to war, they say, they'd enlist.

Anyway, says Chuck Hendsch, president of the National Professional Paintball League, the explosion of paintball's popularity has more to do with the world's largest retailer than with war. "Paintball was only introduced into major sporting goods retailers in 1997, and in Wal-Mart in 1995," he says. He also notes that a case of paintballs that used to cost $125 now sells for $50.

Gaines, one of the game's creators, once said paintball could be seen "as a metaphor for the efficacy of teamwork, for universal cause and effect and for the manner in which consequences evolve from sequential decisions. And some people will even tell you that it is a sure and ugly metaphor for war. We don't believe that is so, but I am not out to argue the point here."

In the parking lot of San Diego's Qualcomm Stadium, the National Professional Paintball League has set up a campus of vendor tents, sound stages and portable bleachers for the fourth of five events that will decide the Super 7 World Series of Paintball. Six turf fields are spread over acres of pavement. Two hundred teams from as far away as Stockholm are jammed into area hotels. Preliminary-round games for amateur and semi-pro divisions are scheduled to begin Friday, and 18 professional squads, including Dynasty, are slated to play the first of their eight opening-round matches Saturday morning.

To win a game, a team must eliminate all seven of the other side's players and capture the opposing flag in less than seven minutes. The teams that survive the first two days return to compete for the $25,000 prize pot.